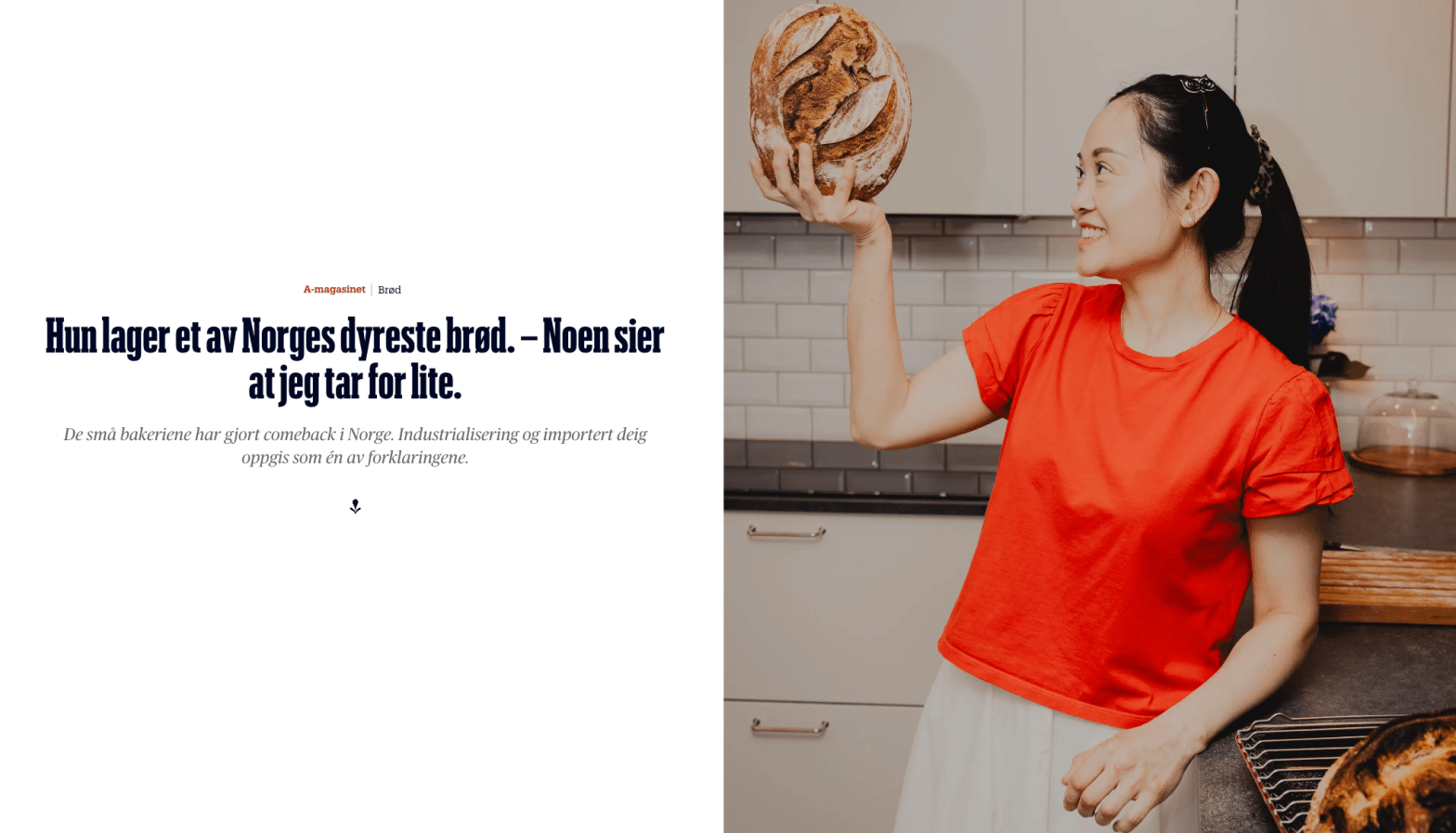

I am so thrilled to share that A-magasinet has published an article about my sourdough baking business! It’s an honor to be featured in such a renowned local magazine, and I’m excited to see my story distributed all over Norway. Big thanks to Aftenposten for this incredible opportunity. Check out the article and join us in celebrating the joy of sourdough!

Here’s the English translation from the article (using ChatGPT):

Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread

For 170 Kroner

IN A BASEMENT APARTMENT in Frogner, Oslo, baking is underway. Small buckwheat nuts are ground and mixed with flour and water. Seeds and coconut are folded in. Malaysian May Goh (44) sprints from dough to dough, sweeping away flour like a whirlwind.

“Sorry, there’s a lot of mess when you bake!”

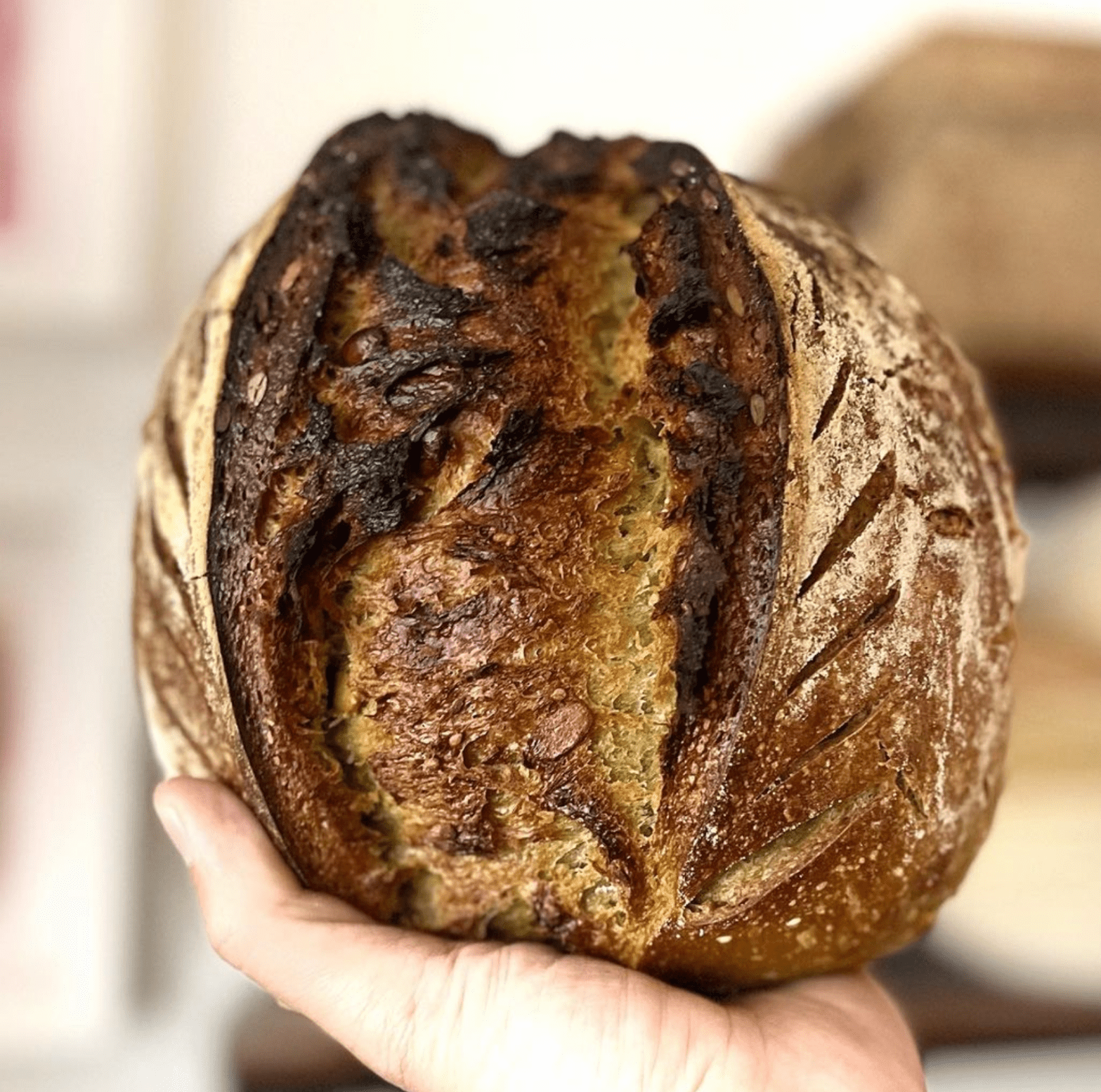

Soon, the small oven smells of freshly baked bread. She carefully pulls out a dark brown loaf and sets it to cool. This is her buckwheat bread, nearly a kilo in weight, particularly rich in protein, and developed at the request of a customer who trains a lot. It’s the most expensive item she sells from her home bakery, Frogner Kitchen.

“I haven’t received feedback that it’s too expensive,” says Goh. “Some say I charge too little.”

Emerging in Small Towns. You might have noticed it: in Norwegian small towns and city streets, they are popping up like bubbles in a juicy focaccia: artisanal bakeries, bakehouses, and home bakers.

Are we on the verge of regaining a bakery culture after most specialty shops have been swallowed by grocery chains?

At least a new undergrowth of small bakeries is sprouting in our country, explains editor of the industry website Bakeri.net, Oddbjørn Roksvaag. He has written about the bakery and confectionery industry for nearly 30 years and is more than averagely interested in bread. Roksvaag covers the industry’s development and sees the establishment of 5 to 20 new businesses each month, with far fewer bankruptcies.

“Many want to enter the industry, driven by a passion for food and a desire to do things themselves. It provides more diversity and a better selection for customers,” says Roksvaag.

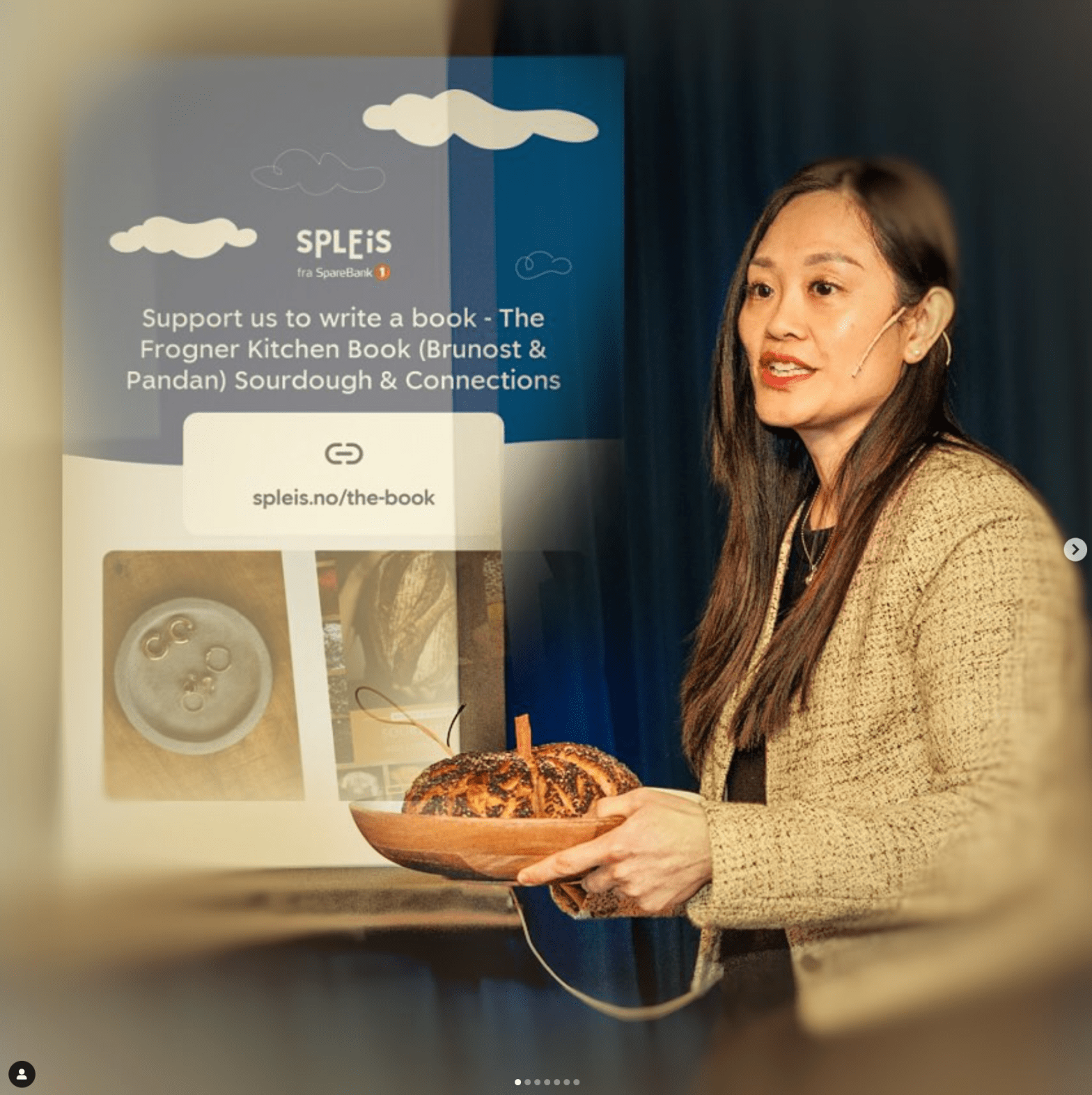

For May Goh, it started when her husband got a job in Norway. She followed and needed something to do. When she posted pictures of the bread she baked on Instagram, some asked to buy it. During the pandemic, she decided to give it a try. Today, she bakes 150-200 loaves a week – for individuals, a restaurant, a deli, and a company offering lunch to its employees. Her home kitchen has been expanded with a proofing cabinet and a baking oven. She has received approval from the Norwegian Food Safety Authority. Her next project is a cookbook focusing on baking with Norwegian and international ingredients.

Finding time to sleep is challenging, she says with a laugh. “I’m always afraid the dough will overproof, as I have no backup plan.”

Goh has two young daughters and schedules her work into two fixed sessions daily: one while the girls are at school, and one after they go to bed in the evening. In the middle of the day, she delivers bread herself, which has had a positive side effect: she feels she has baked her way into Norwegian society.

“I meet many different customers, and some of them become friends.”

But small-scale production is costly. Therefore, she has to charge more than the baker on the corner. Bread prices start at 72 kroner, with the buckwheat bread at 170 kroner being the most expensive A-magasinet has found in Norway. As we will see, this is above the pain threshold for many. Others seemingly have no limits on what they will pay in the pursuit of the best bread.

Scoring. May Goh scores sourdough loaves to control how they crack when they rise in the oven. All bread for Frogner Kitchen is made in this home kitchen.

Special Equipment. The proofing cabinet was made by her husband. The sourdough rests there overnight.

Garnish. The garlic bread is garnished with a slice of lemon before it goes into the oven.